The development of heraldry

The first of the English “Rolls of Arms” date to about 60 years after the reign of Richard the Lionheart ( 1189 – 1199). Before there was anything resembling a Herald’s college in England or elsewhere in Europe, collections of arms had been written down in various forms, sometimes by heralds who were interested in making such collections, sometimes by scribes and recorders who found their rolls useful in aiding their memories at jousting tournaments and other official gatherings of nobles and knights.

The first of the English “Rolls of Arms” date to about 60 years after the reign of Richard the Lionheart ( 1189 – 1199). Before there was anything resembling a Herald’s college in England or elsewhere in Europe, collections of arms had been written down in various forms, sometimes by heralds who were interested in making such collections, sometimes by scribes and recorders who found their rolls useful in aiding their memories at jousting tournaments and other official gatherings of nobles and knights. England is especially rich in these early rolls, it was a Scotsman, J. Storer Clouston, who wrote “ The good fortune of England in preserving so much of her past is nowhere more conspicuous than in her great collections of heraldic rolls or lists of nobles, knights , and squires, with the arms the anciently bore, from the middle of the 13th century onwards. Ours in Scotland begin so comparatively late as the 16th century, the earliest records dating to the 1540’s”. Particulars are available of 100 major rolls in England which date from 1250 to the early 1500’s, just before the beginning of the Heralds’ Visitation.

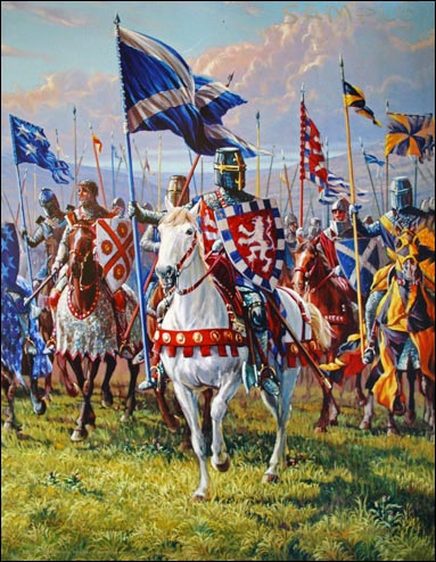

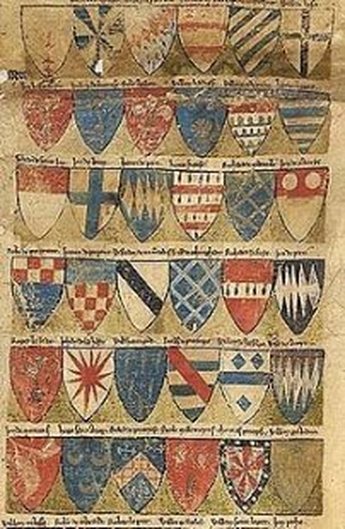

Several of the earliest heraldic rolls are as a result of wars between England and Scotland. The Falkirk Roll gives the arms of those who served under Edward I at the battle of Falkirk in 1298. The arms of 111 people are described in this roll. They are divided into those whose banners were in the vanguard, or in one of the four “battles” into which the army at Falkirk was divided. Thus the arms were borne on the banners of these outstanding persons, and as we see the list of those involved we can picture a scene of great awe as the vanguard and the four succeeding lines of battle approached the narrow plain where the Scots, led by William Wallace, were waiting for them. Many of the most famous names in England at the time appear on this list, among them Percy of Northumberland, Wake of Lincolnshire, Fitzwilliam, Hastings, Moulton, Despenser, Clifford, Basset, and De Vere, Earl of Oxford. Another very interesting early heraldic roll dates from the reign of Edward II ( 1284 – 1387 ), and is known as The Great Parliamentary or Bannerets Roll dating from about 1312. It contains the names and arms of 1,120 people. The roll is divided by county. One of the most fascinating of all of the rolls is that of The Siege of Caerlaverock. It is written in Norman French, the language of Heraldry, and relates to the siege and capture within 36 hours of a small castle in Dumfriesshire, Scotland in the year 1300 during the July campaign of that year by King Edward I. The author of the roll describes in great detail the arms of those present at the siege. He describes 87 banners and 106 coats of arms ( usually banner and shields portrayed the same arms). There has been some conjecture that the author was a herald in the service of King Edward. The roll shows that after 150 years of existence as a science, heraldry was in good shape. It was a useful science because of it’s usefulness in war. The management of the charges borne on the shield was perfectly carried out. It had to be, or heraldic devices would not have fulfilled their function.

Another very interesting early heraldic roll dates from the reign of Edward II ( 1284 – 1387 ), and is known as The Great Parliamentary or Bannerets Roll dating from about 1312. It contains the names and arms of 1,120 people. The roll is divided by county. One of the most fascinating of all of the rolls is that of The Siege of Caerlaverock. It is written in Norman French, the language of Heraldry, and relates to the siege and capture within 36 hours of a small castle in Dumfriesshire, Scotland in the year 1300 during the July campaign of that year by King Edward I. The author of the roll describes in great detail the arms of those present at the siege. He describes 87 banners and 106 coats of arms ( usually banner and shields portrayed the same arms). There has been some conjecture that the author was a herald in the service of King Edward. The roll shows that after 150 years of existence as a science, heraldry was in good shape. It was a useful science because of it’s usefulness in war. The management of the charges borne on the shield was perfectly carried out. It had to be, or heraldic devices would not have fulfilled their function.

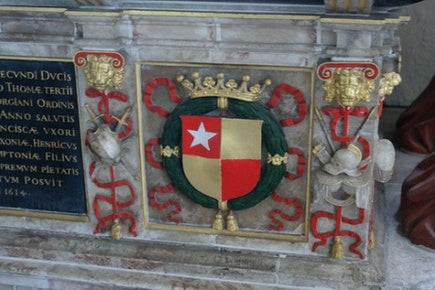

The Knights who used these heraldic devices arranged their armorial devices themselves without recourse to kings or heralds. Sometimes disputes arose as to the ownership of early coats of arms, for example Brian FitzAlan bore: Barry or and gules, which was the subject of a dispute between him and Hugh Pointz, who bore the same arms at the Siege of Caerlaverock. Ralph de Monthermer married Joan, the daughter of Edward I, in the process acquiring the earldoms of Gloucester and Hereford. At the siege Ralph bore a banner with the arms of Clare ( his wife’s first husband’s arms) or three chevronels gules. He bore on his shield his own arms, or an eagle displayed vert. John de Cromwell used his own arms azure a lion rampant double queued ( 2 tails ) argent crowned or, but from other manuscripts from the time period we know that on some occasions he used the arms of the house of Vipoint, gules, six annulets or, because his wife was an heiress of that family.

Ralph de Monthermer Arms

In England during the reign of Edward I ( 1239 – 1307 ), the language spoken in his court was French. Words such as Argent ( Silver), and Azure ( blue) were part of common speech. What came to be known as the blazon, the language of Heraldry, is derived for the most part from the specialized language of artists. To describe a shield exactly required a scientific approach to the language used, and the artisans tasked with creating the coat of arms for the knight or nobleman developed the heraldic language as we know it today. This language was one which was very new in Edward I’s day and was full of inconsistencies. In the Rolls of Edward 1, the noted American heraldic expert Gerald J. Brault notes “it was a matter of indifference to the early compilers whether they blazoned a charge a bend or a baston, a canton or a quarter, an indented or an engrailed cross, a mullet or an estoile, a pale or a pile: I use only the first of these terms having the same meaning. Crosslets were arbitrarily painted in a variety of ways, botonny, cross crosslet, fitchy, paty, plain, etc.: I say crusily for all such semy fields. . . . Compony, which designates a single row of checkers in early as well as present-day heraldry, is used here, but the expression counter-compony for a double row is a later innovation and has been omitted in favor of the medieval term checky.”

In England during the reign of Edward I ( 1239 – 1307 ), the language spoken in his court was French. Words such as Argent ( Silver), and Azure ( blue) were part of common speech. What came to be known as the blazon, the language of Heraldry, is derived for the most part from the specialized language of artists. To describe a shield exactly required a scientific approach to the language used, and the artisans tasked with creating the coat of arms for the knight or nobleman developed the heraldic language as we know it today. This language was one which was very new in Edward I’s day and was full of inconsistencies. In the Rolls of Edward 1, the noted American heraldic expert Gerald J. Brault notes “it was a matter of indifference to the early compilers whether they blazoned a charge a bend or a baston, a canton or a quarter, an indented or an engrailed cross, a mullet or an estoile, a pale or a pile: I use only the first of these terms having the same meaning. Crosslets were arbitrarily painted in a variety of ways, botonny, cross crosslet, fitchy, paty, plain, etc.: I say crusily for all such semy fields. . . . Compony, which designates a single row of checkers in early as well as present-day heraldry, is used here, but the expression counter-compony for a double row is a later innovation and has been omitted in favor of the medieval term checky.”

To make their job easier, as the number of shield designs grew (by the end of the Middle Ages, Brault notes, there were 800,000 of them), heralds began to compile (or convinced the court clerks to compile — it’s not clear who did the actual work) the rolls of arms that form the basis of Brault’s study. There are painted rolls, which show actual colored images of rows of shields, and blazoned rolls, where the shields are only described in the language of heraldry. Some are actual scrolls of vellum, up to ten feet long; others have been cut apart and rebound as books; still others are later copies in book form. About 350 of the original medieval armorials, or heraldic rolls are still in existence today and they contain about 80,000 coats of arms. Of these 350 rolls 130 are for England alone. Although rolls of arms were compiled in France and England by the mid 13th century, the reign of Edward I, with 18 rolls surviving was viewed as the golden age of Heraldry, not only in England but in all of Western Europe.

The Heraldic Rolls of the early middle ages were not confined to England only. Early examples of Heraldic Rolls from elsewhere in Europe include The Wijnbergen Roll ( a Flemish roll dating from about 1280), The Codex Manesse ( A Roll from the early 1300’s), and the Zurich Wappenrolle ( mid 1300’s). The Heraldic Rolls of the early middle ages were not confined to England only. Early examples of Heraldic Rolls from elsewhere in Europe include The Wijnbergen Roll ( a Flemish roll dating from about 1280), The Codex Manesse ( A Roll from the early 1300’s), and the Zurich Wappenrolle ( mid 1300’s).

The Heraldic Rolls of the early middle ages were not confined to England only. Early examples of Heraldic Rolls from elsewhere in Europe include The Wijnbergen Roll ( a Flemish roll dating from about 1280), The Codex Manesse ( A Roll from the early 1300’s), and the Zurich Wappenrolle ( mid 1300’s).

The Wijnbergen Roll is the oldest known French heraldic manuscript. It was completed in 23 parts, the first, showing arms of the vassals of the Ile de France under Saint Louis, can be dated 1265-1270; the second, an armorial of the north of France, the Low Countries and Germany under Philippe III, is more difficult to date, but is a complement to the first, 1270-1285. The roll is entirely painted, with the text in French, containing a total of 1312 shields in the two parts. The Codex Manesse, image above, also known asGroße Heidelberger Liederhandschrift is a manuscript begun around 1300 and completed in 1340. The manuscript was produced in Zürich, at the request of the noble Manesse family. The Zurich Wappenrolle, image below, derives from the place where it is kept: the Burgerbibliothek (= citizens library) Zurich. Many of the coats of arms are from the area around Lake Constance it can be concluded that the roll was made there.

None of these rolls are official armorials, they were created by interested individuals, artisans, and professional heralds and were created at the request of patrons. All three rolls contained full color painted representations of the coat of arms, and copies of all three have been made over the centuries, with copies in various museums around the world today.

Zurich Roll

Wijnbergen Roll

Although true Heraldry “ the systematic use of hereditary devices centered on the shield” officially originated only in the second quarter of the 12th century, by the end of the middle ages there were approximately 800,000 coats of arms recorded, many more than even the most knowledgeable of herald could memorize. Heraldic devices served not only to identify a knight in battle but were also legal marks on seals, boundary markers on property etc. This vital material was recorded Heraldic armorials or rolls. In addition to the Rolls mentioned in the two previous posts there are another 17 of importance from this early period, all from Great Britain.

Although true Heraldry “ the systematic use of hereditary devices centered on the shield” officially originated only in the second quarter of the 12th century, by the end of the middle ages there were approximately 800,000 coats of arms recorded, many more than even the most knowledgeable of herald could memorize. Heraldic devices served not only to identify a knight in battle but were also legal marks on seals, boundary markers on property etc. This vital material was recorded Heraldic armorials or rolls. In addition to the Rolls mentioned in the two previous posts there are another 17 of importance from this early period, all from Great Britain.

The Rolls are Heralds Roll ( 1279), Dering Roll ( 1280), Camden Roll ( 1280), St. George’s Roll ( 1280), Charles’ Roll ( 1285), Segar’s Roll (1285), Lord Marshal’s Roll (1295), Collins’ Roll (1296), Guillim’s Roll ( 1295-1305), Galloway Roll (1300), Smallpece’s Roll (1298-1306), Stirling Roll (1304), Nativity Roll (1307-1308), Fife Roll ( early 1300’s), Sir William le Neve’s Roll (early 1300’s).Twelve of these rolls are illustrated by shields painted in full color, the remainder contain the blazons only ( the written description of each coat of arms). The Camden Roll contains both Blazon and painted illustrations. Most of the bearers of arms represented in these rolls are Englishmen, although there are Welsh Scottish and Irish knights to be found as well as a considerable number of continental European knights and nobles, such as the Gascons and Savoyards who were attached to King Edwards court at one time or another.

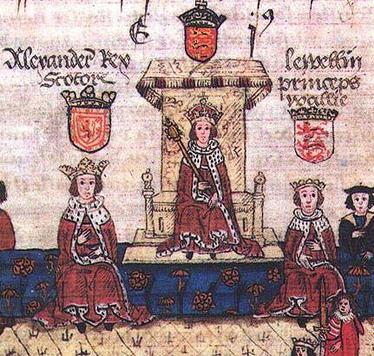

Five of the Heraldic Rolls ( Herald’s, Camden, Segar’s, Lord Marshal’s and Smallpece’s) begin with a listing of kings graded according to an arbitrary hierarchy. Herald’s and Segar’s place Prester John first, Camden’s and Smallpece’s have The King of Jerusalem first, Lord Marshal’s has the Emperor of Constantinople in first place. Interestingly, the King of England is ranked number 3 in the Smallpece Roll and number 7 in the Camden and Segar Rolls and number 9 in Herald’s Roll. On the other hand the arms of the King of England are listed first in four of the rolls ( St. George’s, Collin’s, Guillim’s, Galloway).

The first regent to make extensive use of Heraldry, both on and off the battlefield was Edward I (1239-1307). In his twenties he joined a rebellion against his father, led by Simon de Montfort, but soon switched sides. He then spent many years traveling on the Crusades and did not return until 1274, after his father’s death. The early years of Edward’s reign were relatively peaceful, but by 1277 he was at war with Llywelyn ap Gruffydd of Wales. In 1282, Edward took by right of conquest the title “Prince of Wales” that the current heir to the British throne, Prince Charles, still holds.

The first regent to make extensive use of Heraldry, both on and off the battlefield was Edward I (1239-1307). In his twenties he joined a rebellion against his father, led by Simon de Montfort, but soon switched sides. He then spent many years traveling on the Crusades and did not return until 1274, after his father’s death. The early years of Edward’s reign were relatively peaceful, but by 1277 he was at war with Llywelyn ap Gruffydd of Wales. In 1282, Edward took by right of conquest the title “Prince of Wales” that the current heir to the British throne, Prince Charles, still holds.

Meanwhile, the Scots allied themselves with the French, who attacked Edward’s possessions in Gascony. Edward went to war in France in 1294, but lost. He put down another uprising in Wales, then sent his army against the Scots, who surrendered in 1296. The Stone of Scone, where Scottish kings had been crowned for centuries, was taken to Westminster Abbey and encased in a carved oak throne still used as the British coronation chair.

But in 1297, the Scots rebelled again, this time led by the William Wallace of Braveheart fame. The Scottish wars, including the Siege of Caerlaverock and the battle at the River Cree, seemed to end in 1306, when Braveheart was beheaded. However in an astonishing turnabout, on 10 February 1306, Robert de Bruce, earl of Carrick, who had been supporting the English, murdered John Comyn of Badenoch [whom Edward had set on the Scottish throne] and, a month later, was crowned king at Scone. Edward was on his way to a battle with Bruce when he died in 1307, aged 66.

Beside him, in all these battles, Edward I would have had a herald, naming the enemy, finding upon the field Simon de Montfort Gules, a lion rampant with a forked tail argent, Llywelyn ap Gruffydd Quarterly or and gules, four lions rampant guardant counterchanged, or Robert the Bruce Argent, a saltire and a chief gules.

The first heralds to be mentioned, beginning in the 1170′s, were mere announcers at tournaments, for years grouped in the royal payrolls along with minstrels, trumpeters, and harpers. As the use of Heraldry spread, the importance of it as a science became more widely recognized. As the number of knights grew and the importance of heraldry as a means of keeping friend and foe straight increased, heralds rose in stature to be considered ambassadors and great men in their own right.

Originally, bearers of coats of arms were knights who could be called up for military duty. A knight’s rank was not readily apparent from his shield. In the reign of Edward I. the heraldry of these individuals does not appear to have been any different from that of their social superiors. King Edward’s three lions passant guardant or on a field of gules (three gold lions, down on all fours on a red shield) was no more elaborate (or simple) than his enemy, William Wallace’s gules, a lion rampant argent (red, with a white lion up on its hind legs), or Robert the Bruce’s saltire and chief ofgules on a field of argent (a white shield bearing a large yellow Saint Andrew’s cross, with a yellow band across the top).

The Rolls of Arms, which were painstakingly created by the Heralds of the time, were long narrow strips of parchment, on which were written lists of the names and titles of the knights and squires as well as full descriptions of their armorial insignia. The exact circumstances under which the rolls were created is unknown, but the accuracy and veracity of them has been proven beyond doubt by careful and repeated comparison with seals and other documents from the time period. It is obvious from the similarity in description between the rolls that the early Heralds from the time of Edward I had framed some system for the regulation of their work, and this is what raised their art form to a science.. The Heralds of the time had decided upon certain terms and rules for describing heraldic devices and figures, and had established laws to direct the granting, the assuming, and the bearing of arms.

Edward I

Back to menu

Shop Our Products

CTA Text

-

-

Bring Your Idea to Life

Start with a personalized consultation, sharing your vision and preferences with our expert design team. With over 20 years experience we have the knowledge and craftsmanship to create a unique piece of jewelry that will be cherished for generations to come.