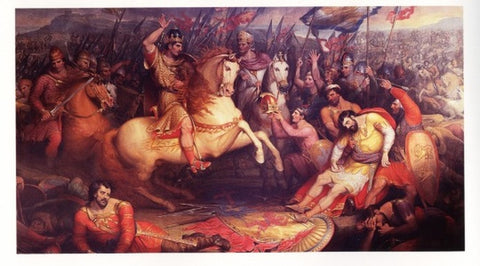

The Battle of Hastings and The Norman Conquest, part 1

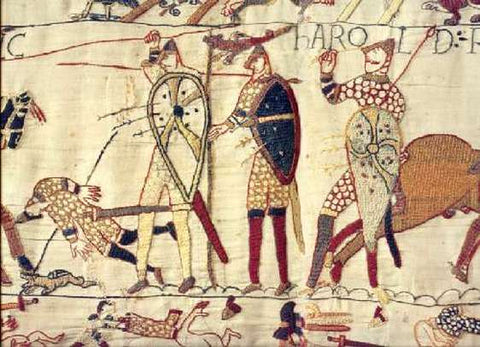

When William, Duke of Normandy, wrested control of England from King Harold, heraldry was not widely practiced in even the more advanced societies in Europe. The Bayeux Tapestry, the famous pictorial record of the Norman invasion, shows decorated shields and banners, and attempts have been made to identify individuals by these shields but with not very convincing results. However Wace, writing at the time of Henry II stated:

‘They ( the Normans) had shields on their necks and lances in their hands, and all had made cognisances that one Norman might know another by, and that none others bore, so that no Frenchman might kill another.”

It is unlikely that Wace meant that the Normans bore individual cognisances, or shields, but rather there were one or two emblems in use throughout in order to distinguish William’s followers as a whole from the Saxons. His identification of all of the members of an army by a distinctive figure was no new thing. We read in St. Olaf’s Saga that at the battle of Niesse, 50 years before the battle of Hastings:

“ the most of his men had white shields, on which the holy cross was gilt; but some had painted it in blue and red.”

The reason for this clearly appears in the account of Olaf’s last battle, in 1030, when the King ordered:

“ We will have all our men distinguished by a mark, so as to be a field token upon their helmets and shields, by painting the holy cross thereupon with white colour. When we come into battle we shall all have one counter-sign and field-cry, ‘Forward, forward, Christ-men ! Crossmen ! King’s men!’”

The King himself had “ a white shield on which the Holy Cross was inlaid in gold.” So we may assume that at the Battle of Hastings in 1066 the devices on the Norman shields, if they were anything more than merely decorative, had a partisan rather than a personal significance. The Bayeux Tapestry shows us that a dragon was a favorite figure on the Norman shields. But the dragon was clearly the English emblem. It was around the banner of the Golden Dragon of Wessex, known as “ The German Dragon” of the so-called prophecies of Merlin:

“ The German dragon shall hardly get to his holes……for a people in wood and in iron coats shall come and revenge upon him his wickedness. They shall restore the ancient inhabitants to their dwellings, and there shall be an open destruction of foreigners……After this shall succeed two dragons, whereof one shall be killed by the arrow of envy, but the other shall return under the shadow of a name. Then shall succeed the Lion of Justice, at whose roar the Gallican towers and the island dragons shall tremble” – Geoffrey of Monmouth

Why would the Normans display their enemy’s emblem? William always claimed to be King of the English by right, and the prevalence of the dragon on the shields of his followers suggests that he may have deliberately adopted the emblem of the English as an expression of his claim to be their lawful king.

‘They ( the Normans) had shields on their necks and lances in their hands, and all had made cognisances that one Norman might know another by, and that none others bore, so that no Frenchman might kill another.”

It is unlikely that Wace meant that the Normans bore individual cognisances, or shields, but rather there were one or two emblems in use throughout in order to distinguish William’s followers as a whole from the Saxons. His identification of all of the members of an army by a distinctive figure was no new thing. We read in St. Olaf’s Saga that at the battle of Niesse, 50 years before the battle of Hastings:

“ the most of his men had white shields, on which the holy cross was gilt; but some had painted it in blue and red.”

The reason for this clearly appears in the account of Olaf’s last battle, in 1030, when the King ordered:

“ We will have all our men distinguished by a mark, so as to be a field token upon their helmets and shields, by painting the holy cross thereupon with white colour. When we come into battle we shall all have one counter-sign and field-cry, ‘Forward, forward, Christ-men ! Crossmen ! King’s men!’”

The King himself had “ a white shield on which the Holy Cross was inlaid in gold.” So we may assume that at the Battle of Hastings in 1066 the devices on the Norman shields, if they were anything more than merely decorative, had a partisan rather than a personal significance. The Bayeux Tapestry shows us that a dragon was a favorite figure on the Norman shields. But the dragon was clearly the English emblem. It was around the banner of the Golden Dragon of Wessex, known as “ The German Dragon” of the so-called prophecies of Merlin:

“ The German dragon shall hardly get to his holes……for a people in wood and in iron coats shall come and revenge upon him his wickedness. They shall restore the ancient inhabitants to their dwellings, and there shall be an open destruction of foreigners……After this shall succeed two dragons, whereof one shall be killed by the arrow of envy, but the other shall return under the shadow of a name. Then shall succeed the Lion of Justice, at whose roar the Gallican towers and the island dragons shall tremble” – Geoffrey of Monmouth

Why would the Normans display their enemy’s emblem? William always claimed to be King of the English by right, and the prevalence of the dragon on the shields of his followers suggests that he may have deliberately adopted the emblem of the English as an expression of his claim to be their lawful king.

BAYEUX TAPESTRY, THE DEATH OF HAROLD